WHAT IS A TRIGGER POINT?

If you’re an athlete, you are probably familiar with the term trigger point. Maybe you’ve been told that you have trigger points in your upper back or your calves, and maybe you’ve been instructed to buy a special ball to release said trigger points or to do a lot of foam rolling. But do you actually understand what a trigger point is?

A trigger point is NOT simply a synonym for a tight muscle.

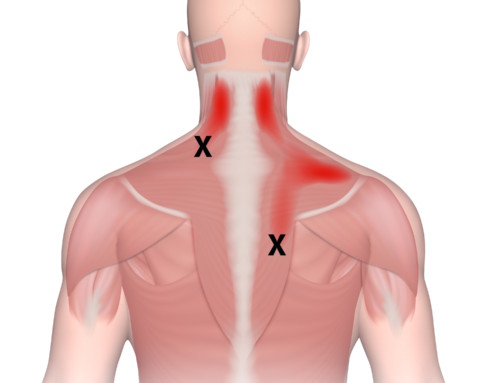

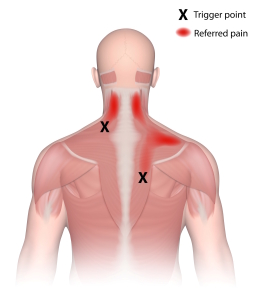

To be a trigger point, a taut muscle band must meet a number of criteria. A trigger point is defined as “a highly irritable localized spot of exquisite tenderness in a nodule in a palpable taut band of muscle tissue.”1 So a trigger point is a small part of the muscle, not an entire muscle in spasm. Other characteristics include:

- A trigger point must refer pain (or other symptoms) when compressed.

- The location of the point and the pattern of referral are predictable.

- A trigger point exhibits a local twitch response when needled.

- Pain referred from a trigger point is deep, achy, and difficult to pinpoint.

- Clinical characteristics of trigger points include pain upon muscle contraction and limited range of motion.

- EMG studies in muscles with active trigger points indicate muscle weakness: the muscle starts out fatigued, it fatigues more rapidly and becomes exhausted sooner than muscles not harboring trigger points.2

- Trigger points are often found in clusters or chains, and an active trigger point in one muscle can activate satellite trigger points in another muscle.

Ok, not too exciting, right? But wait! There’s this one other thing:

TRIGGER POINTS ARE FASCINATING BECAUSE IN MANY WAYS THEY MAKE NO SENSE AT ALL.

-

Trigger point referral patterns follow no logical pattern whatsoever!

The referred pain does not follow dermatomes, and it cannot be explained by findings on a neurological examination. This means that a trigger point in a muscle can refer pain into an area of the body that is innervated by a completely different spinal nerve! Sometimes these pain referral patterns get pretty crazy. For instance, a certain trigger point in your soleus (calf) can refer pain into your sacrum (low back). How often do you look to your calf to relieve the pain in your butt?

-

Trigger points refer some really weird symptoms other than pain:

Trigger points in abdominal muscles can cause heart arrhythmia, nausea, diarrhea, appetite loss, projectile vomiting, and urinary incontinence. Trigger points can also have autonomic effects that verge on the unbelievable: red eyes, excessive tearing, blurred vision, tinnitus, droopy eyelids, excessive salivation, persistent nasal secretion, and goose bumps. They can cause dizziness and imbalance and distort weight perception of objects you hold.

-

Trigger point pain can be debilitating.

We are not talking about your everyday post-workout muscle soreness. Patients have rated trigger point pain as severe as cystitis, angina, and shingles.3 Pain from a trigger point typically feels deep and achy, although certain movements can sharpen the pain. Trigger point pain can come and go, and it is notoriously difficult to pinpoint its exact location

-

Vitamin deficiencies and metabolic disorders could be to blame.

Trigger points are typically caused by muscle overload, repetitive movement, or postural stress. However, there are a number of nutritional and chemical imbalances that interfere with muscle metabolism and thus perpetuate trigger points.4,5 In particular, inadequate levels of vitamins B1, B6, B12, vitamin C, folic acid, calcium, iron, magnesium, and potassium have been shown to correlate with chronic pain caused by trigger points. Metabolic disorders including hypothyroidism, hypoglycemia, anemia, and high levels of uric acid in the blood may also perpetuate trigger points.

-

There is an uncanny overlap between trigger points and acupuncture points.

One study found a 71% correspondence between the locations of trigger points and classical acupuncture points; another paper found that 92% of the 255 documented trigger points correspond to acupuncture points, and that 79.5 percent have similar pain indications.6,7 In addition, the referral patterns and satellite trigger point chains tend to follow acupuncture meridians.8

While the referral patterns of trigger points often seem to make no sense at all, acupuncture meridians (developed more than 2,000 years ago) often map these referrals out perfectly. Clearly, the ancient Chinese were astute enough to recognize the importance of many common trigger point locations and to include them in their acupuncture charts.

Stay tuned for Trigger Points Part II, where I will cover how trigger points affect athletic performance and some of the best (and worst!) ways to treat them.

References:

- Travell, Janet G. “Travell and Simons’ Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual, vol. 1. Upper Half of Body.” (1983): 23.

- Headley, B. J. “Evaluation and treatment of myofascial pain syndrome utilizing biofeedback.” Clinical Electromyography for Surface Recordings. Nevada City, NV: Clinical Resources (1990): 235-254.

- Skootsky, SAMUEL A., Bernadette Jaeger, and Robert K. Oye. “Prevalence of myofascial pain in general internal medicine practice.” Western Journal of Medicine2 (1989): 157.

- Travell, Janet G. “Travell and Simons’ Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual, vol. 1. Upper Half of Body.” (1983): 186-213.

- Travell, Janet G. “Travell and Simons’ Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual, vol. 1. Upper Half of Body.” (1983): 213-220.

- Melzack, Ronald, Dorothy M. Stillwell, and Elisabeth J. Fox. “Trigger points and acupuncture points for pain: correlations and implications.” Pain1 (1977): 3-23.

- Dorsher, Peter T. “Can classical acupuncture points and trigger points be compared in the treatment of pain disorders? Birch’s analysis revisited.” The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine4 (2008): 353-359.

- Hong, Chang-Zern. “Myofascial trigger points: pathophysiology and correlation with acupuncture points.” Acupuncture in Medicine1 (2000): 41-47.